A corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum), also known as titan arum, has bloomed at the U.S. Botanic Garden. It is the first bloom for the plant, which was propagated by a leaf cutting from another USBG A. titanum. Photo at right shows the peak bloom as of June 25, 2021.

A corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum), also known as titan arum, has bloomed at the U.S. Botanic Garden. It is the first bloom for the plant, which was propagated by a leaf cutting from another USBG A. titanum. Photo at right shows the peak bloom as of June 25, 2021.

As the Conservatory was closed, visitors were able to watch the corpse flower bloom growing on high-definition live video camera feed. The plant opened in peak bloom on the evening of June 24, 2021.

About the 2021 Corpse Flower Plant

The first Amorphophallus titanum to begin blooming in 2021 (USBG accession #07-1034 C) was propagated by a leaf cutting from an older A. titanum plant in the USBG's collection. This plant was over four years old. The parent plant has bloomed three times - 2013, 2017, and 2019.

The spadix was first seen on June 14, 2021. The plant was measured at 50" in height on that day. See daily height updates in the sidebar. The plant opened in peak bloom on the evening of June 24, 2021, measuring 97.5" in height.

Pollen was collected on June 26, 2021. Some of the pollen was sent to Chicago Botanic Garden for storing and sharing as part of the conservation project (learn more below), and some pollen was stored locally at USBG for future onsite pollination use.

Corpse Flower and Aroid Conservation

The corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum) is listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with an estimation of fewer than 1,000 individuals remaining in the wild. IUCN estimates the population has declined more than 50% over the past 150 years. The main reasons for the decline are logging and the conversion of the plant’s native forest habitat to oil palm plantations.

The U.S. Botanic Garden is participating in conservation work related to Amorphophallus titanum and aroids plants. Diversity amongst the gene pool is important for successful conservation of endangered plants held in ex situ conservation collections such as at botanic gardens. The U.S. Botanic Garden helped fund a conference in partnership with Botanic Garden Conservation International on aroid conservation in 2018 that was attended by botanic garden professionals from around the world. As an offshoot from this, many botanic gardens are participating in a national A. titanum conservation project that is underway, headed by Chicago Botanic Garden.

The goal of the project is to identify and create a database of the genetic makeup of A. titanum plants currently in botanic garden collections. This information will be used to ensure a broadening of the gene pool by creating diversity amongst new offspring by cross-pollination of diverse parent plants. The USBG has gathered and submitted plant material from our A. titanum collection to be added into the database. We hope to be able to acquire pollen based on this project to create diverse offspring. The Garden also plans to collect pollen from this plant to store for future use by other botanic gardens in this project.

What Makes the Corpse Flower Special?

The allure of the corpse flower comes from its great size (it is the largest unbranched inflorescence in the plant kingdom), powerful stink, and fleeting presence. The plants frequently grow up to 8 feet tall in cultivation. Referred to as the corpse flower or stinky plant, its putrid smell is most potent during peak bloom at night into the early morning. The odor is often compared to the stench of rotting flesh. The inflorescence (a collection of flowers acting as one) also generates heat, which allows the stench to travel further. This combination of heat and smell efficiently lures corpse-attracted pollinators, such as carrion beetles and flies, from across long distances.

The corpse flower does not have an annual blooming cycle. The bloom emerges from, and energy is stored in, a huge underground stem called a "corm." The plant blooms only when sufficient energy is accumulated, making time between flowering unpredictable, spanning from a few years to more than a decade. It requires very special conditions, including warm day and night temperatures and high humidity, making botanic gardens well suited to support this strange plant outside of its natural range.

This plant is native to the tropical rainforests of Sumatra, Indonesia, and first became known to science in 1878. In its natural habitat, the corpse flower can grow up to 12 feet tall. Public viewings of this unique plant have occurred a limited number of times in the United States. The U.S. Botanic Garden has displayed blooming corpse flowers in 2003, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2017 (three blooms), and 2020 (two blooms).

Watch the Time Lapse

Watch a time lapse of a previous corpse flower bloom growing, opening, and collapsing here at the U.S. Botanic Garden. You can explore recordings of live Q&A programs, pollination, conservation, and more in this video archive playlist: viewing the full playlist on YouTube.

Join gardener Stephen to find out what clues he used to determine a previous bud (2020) was a bloom and not a leaf:

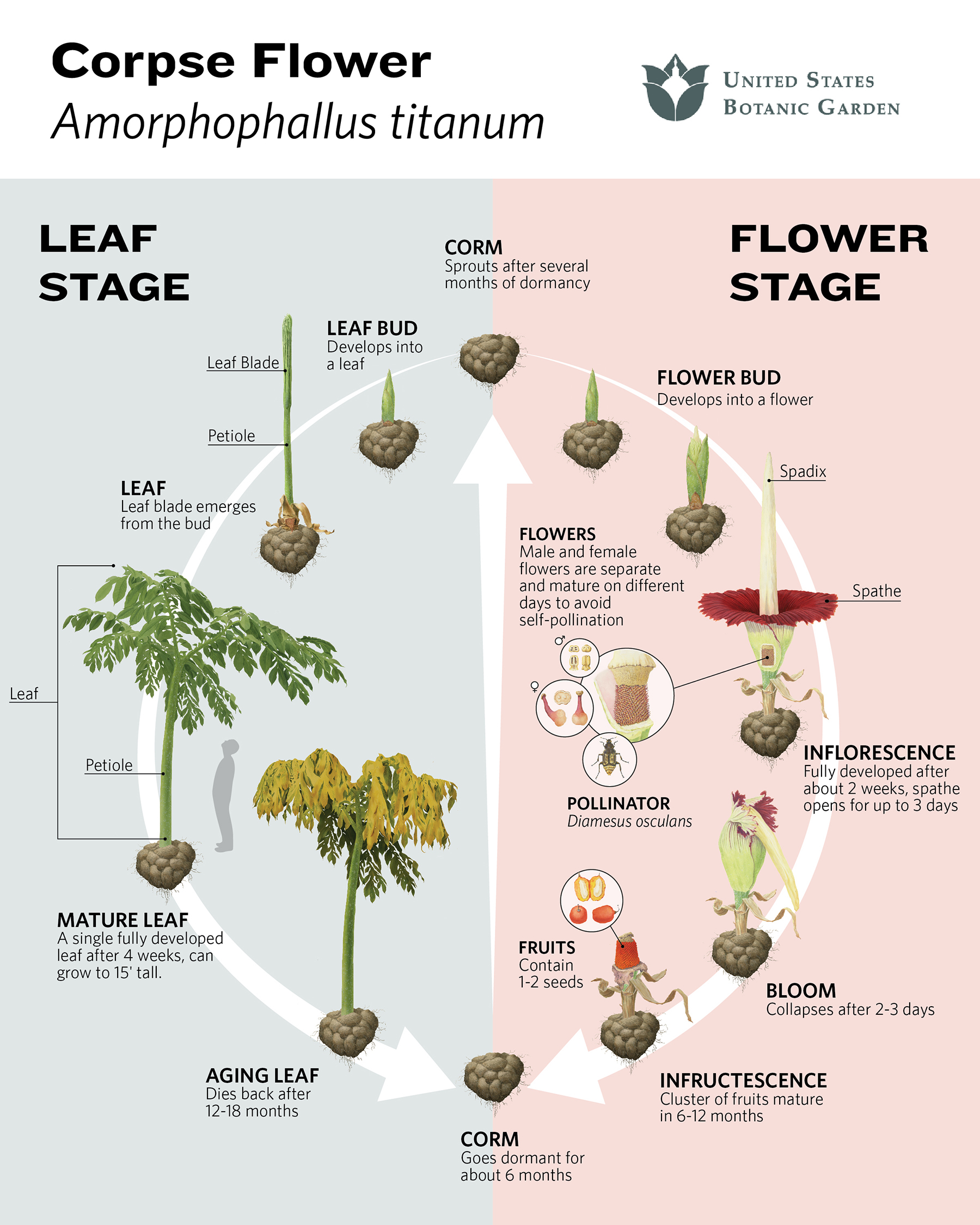

Corpse Flower Lifecycle Infographic (click to see large version):

Chemistry of its smell

Want to learn a bit more about the plant and its unique smell? Check out this great video we helped create:

Corpse flower lifecycle and pollination

Check out this great video we helped create about the corpse flower's lifecycle, smell, and reproduction:

We shared the 2016 plant's life cycle via a live webcam, which has now ended. In addition to this video from the morning it started opening, August 2, 2016, you can find all the live webcam videos on our YouTube channel. If you visited, find your date and see yourself with the corpse flower!

Photo of 2013 corpse flower bloom:

The U.S. Botanic Garden has displayed blooming corpse flowers in 2003, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2017 (three blooms), and 2020 (two blooms). More than 130,000 people came to see the 2017 bloom in person, and more than 650,000 viewers accessed the live webstream.

Learn more about the two 2020 blooms.

Learn more about the three 2017 blooms.

Learn more about the 2016 bloom.

Learn more about the 2013 bloom.